Personal Note: I’ve wanted to get this post up for the longest time and am finally getting around to it! I felt this would be a good time for a historical piece as there is a lot to dive into. You should come back and take a look at the included documents at your leisure as they have some great reading. I’m checking out until the new year but as always, the chatter on the Community never stops.

One of my most enjoyable walking routes near downtown is a stroll up and down North East and North Bloodworth street, mainly through the Oakwood neighborhood. The trees are mature and their presence makes the streets feel cozy. The houses are rich with architecture. I find new and delightful details on every walk it seems.

This section of town offers a lot of history including the possibility of being completely demolished for a highway. Yes, a highway could have been placed along the properties between Bloodworth and East Streets if planners and traffic engineers had their way in the early 1970s.

Raleigh history fans probably already know about this possible highway through Oakwood but I’ve always wanted to dive into those plans for myself. It was a pretty substantial component of a State Government vision for the future.

A vision that never came to be.

You can take a look at the 89-page, 1965 document (pdf format) for yourself as the text and images are fascinating to look at.

In 1958, a State Capital Planning Commission was established to work on plans for a state government complex in downtown Raleigh. A highlight of their work was the 1965 North Carolina State Capital Plan and in its opening letter, Chairman O. Arthur Kirkman states:

This report is the result of two years’ work by the Commission and its consultants. We are confident that it provides the State with an unparalleled opportunity to develop a magnificent State Capital in keeping with our heritage. We hope that you and the citizens of the State will give the recommendations which follow your deepest consideration and support.

The document was only meant to be an advisory plan rather than actual plan for implementation. State, as well as local elected officials, spent years reviewing and critiquing the plans.

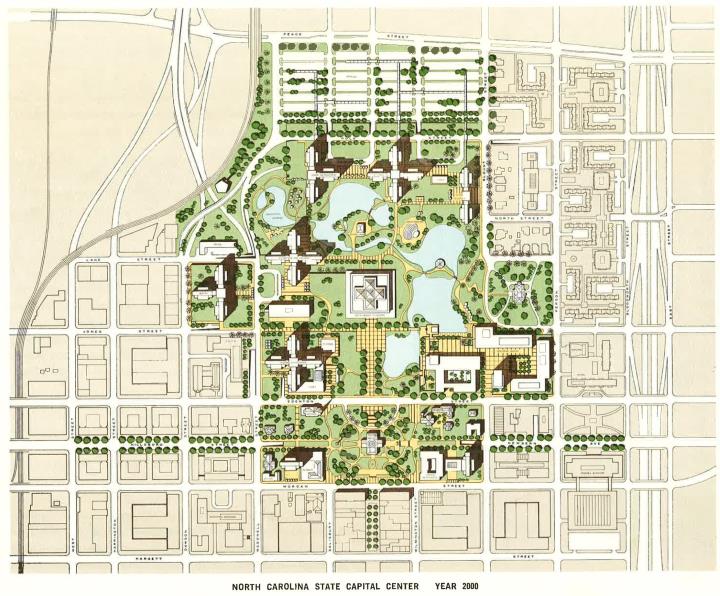

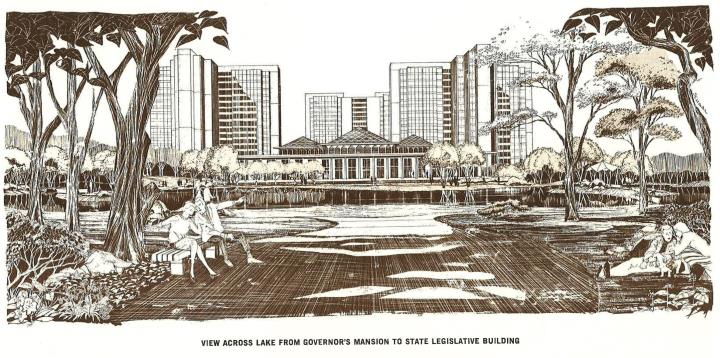

The State Capital complex vision was a pretty stark difference compared to what we have today. Instead of buildings and parking decks along a, more or less, urban grid, the vision involved something you would see in Research Triangle Park. (RTP)

Buildings would be connected with winding walkways. You’d see bridges over lakes and streams. Access would be underground with no streets inside the campus. Decorating the campus would be plazas, fountains, and terraces.

The historic street grid of Raleigh would essentially be removed in exchange for open grassy fields and surface parking lots.

You can see a model of the plan in this rendering below.

It almost seems like the plan was trying to correct a perceived problem with how Raleigh was originally planned and how that plan could no longer accommodate our city’s current and future growth. The original plan for Raleigh, the William Christmas plan, consisted of a grid of streets with five main squares. This plan is still mostly intact in downtown leading up to the 1960s.

From the document:

The often short-sighted steps taken to meet the problems of growth and changing conditions have done great damage to what has remained of the vision of the city’s founders. Intelligent planning can, however, recover much that was lost and provide for orderly, meaningful growth in the future.

The 1965 plan includes many phases of how to acquire land and roll out these concepts so that by the year 2000, there would be a full build out of the government campus.

What makes this document interesting are some of the assumptions and projections made back in 1965. I feel that some still apply today where some are up for debate. How might this have affected downtown Raleigh if even a small portion of the plan was put into place?

The section titled “Future Needs” has some great projections leading up to the year 2000. It makes sense that one of the first things to mention is the growth of the state government employee population.

In 1840 there were but fifteen State employees, exclusive of the General Assembly, all housed in the Capitol building. In 1926 there were approximately 700 persons in State administrative agencies in Raleigh. In 1963 there were more than 5,600 and there can be no doubt that as the population of North Carolina grows, the State will take on many new responsibilities.

By the year 2000, the report estimated that there would be 15,663 state government jobs in Raleigh. I pulled up a 2014 State of Downtown Raleigh report from the Downtown Raleigh Alliance and according to their estimates, the State of North Carolina had 13,000 employees. So we’re not there just yet.

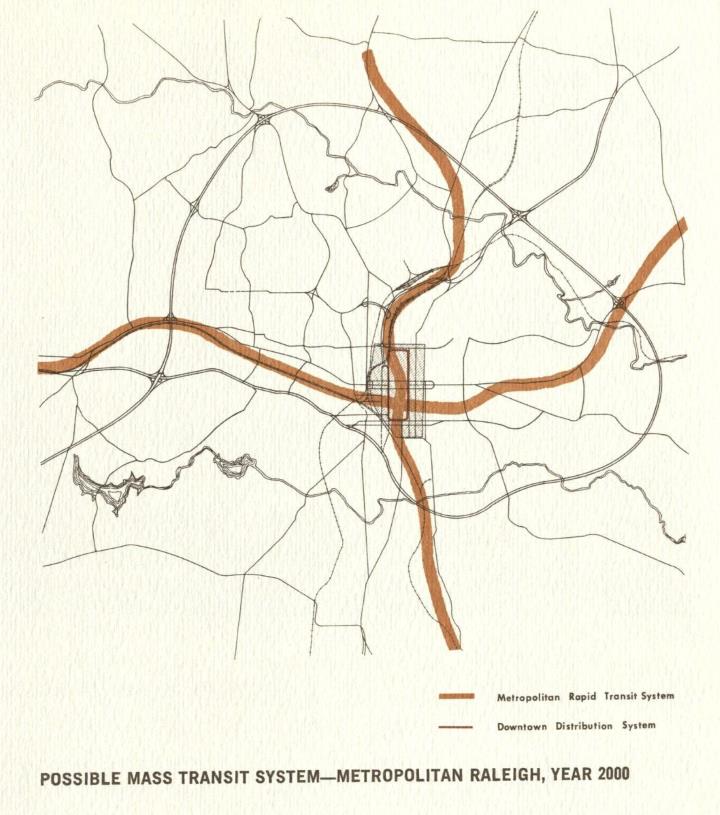

Another interesting prediction was around transportation. The document clearly identifies the dependence on the car to get around the city but predicted alternatives in the future.

Although the automobile is now a prime means of transportation, this will not necessarily be true by the year 2000. Raleigh at present is heavily committed to the automobile and could not now exist without it. In the future, however, the prime means of access to the central city will probably be some combination of private vehicles and mass transportation. Although the foreseeable population levels and densities probably will not justify a rapid transit system, this possibility should be kept in mind. Concentration of employment as proposed in the State Capital Center plan is favorable to mass transit, and similar concentrations along corridors of travel may some day justify a means of transportation other than the automobile. The study now under way may well set some guidelines for the future in this respect.

Attached to this section is a map of mass transit routes that may be possible in the year 2000. I can’t help but laugh a bit seeing this prediction as we are underway now planning a bus-rapid transit system along the very same lines drawn in each cardinal direction outward from downtown Raleigh.

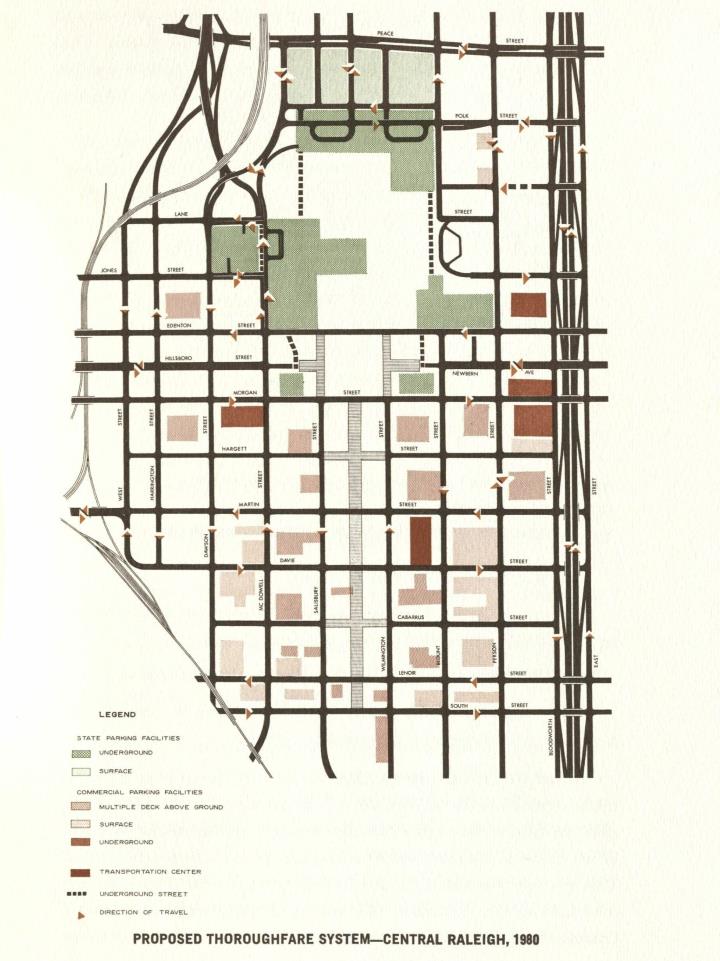

The document mentions that the roads in Raleigh in 1965 were “currently operating at or near capacity during rush hours.” This was seen as a barrier for future growth. “Obviously, this system as it now exists will be able to accommodate little future growth.”

Obviously.

This is the part of the story where the famed freeway through Oakwood comes into play. To alleviate congestion seen on the north side of downtown on Capital Boulevard, then named Downtown Boulevard, some kind of connection was needed on the eastern side.

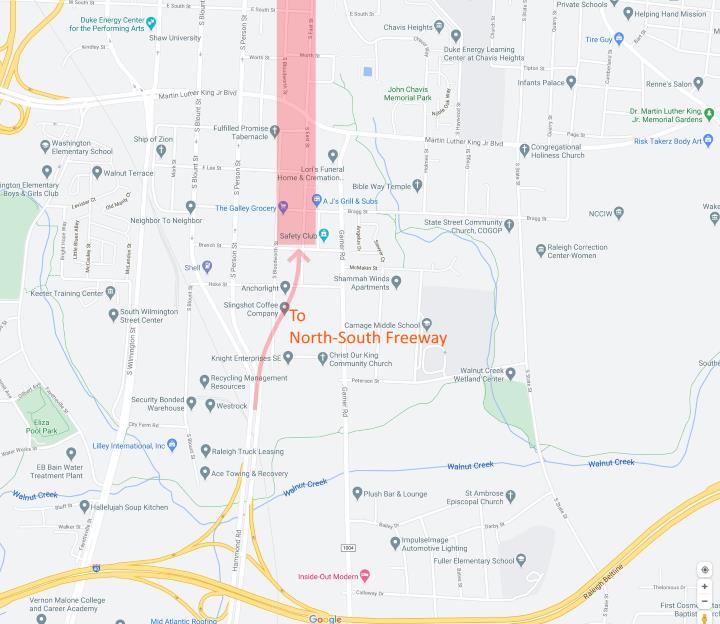

The proposed highway would go through the neighborhoods of Mordecai and Oakwood. It would start with a connection to Wade Avenue on the north and proceed south to Hammond Road, at present day I-40 through the Chavis Heights and South Park neighborhoods.

The highway was envisioned to be built below grade with cross streets bridging over it.

The freeway is depressed below grade at most points to diminish the detrimental effects of noise and glare on the adjacent land. Such a highway is a major gateway to the city and should be given exceptional design attention. Bridges and other structures should be graceful and the landscape attractive, providing shade, protection from glare, and a pleasant setting. Signs and lighting should be carefully and tastefully designed. Land use along the freeways also should be planned so as to enhance the image of the capital city.

A lot of what has been talked about so far never came to fruition. Specifically, the highway on the eastern side of downtown was met with opposition by the neighbors that would be displaced.

We know the end of the story but I took a few extra steps and wanted to see how things played out during that time by taking a look at old newspaper articles. I’d like to share some excerpts below and you can find the article scans at the bottom.

A 1969 News and Observer article talks about plans to acquire all the property along the North-South Freeway:

City Manager W. H. Carper told the councilmen, city planners and traffic engineers that he thinks the biggest problem of “right-of-way encroachments by developers” will be along the proposed north-south freeway route “between East Street and Bloodworth Street.”

Councilman Seby Jones suggested that “if the city could [illegible] funds perhaps strategic corners of property could be bought along the route.”

“That’s a good idea,” said city traffic engineer Don Blackburn.

Because of a lack of funds, the city is unable to buy the property needed to preserve the rights-of-way for the proposed thoroughfare project.

Thoroughfare Plan Studied by Officials – News and Observer – March 21, 1969.

Planning took years and in 1972, The Society for the Preservation of Historic Oakwood was born. At the time, Raleigh didn’t have any historic preservation districts, something that would certainly change soon after.

Jumping to 1974, I found some articles suggesting that elected officials were strongly against such a highway plan. Although the need, real or not, for more roads into and out of downtown was widely agreed upon, the planning commission was looking for alternatives to the North-South Freeway. When discussing a rezoning case in Oakwood:

Planning Commission member Benjamin B. Taylor said the commission could not plan properly for the Oakwood neighborhood because the City Council has made no “commitment” to the continued existence of Oakwood and has left the proposed expressway in the city’s thoroughfare plan for future construction.

Earlier, commission member Spurgeon Cameron had moved that the commission recommend to the City Council the removal of the North-South Expressway from city road plans.

Cameron said it is “some cold, hard, idiotic planning to leave that in the thoroughfare plan.”

But city planning director A. C. Hall advised the commission that rather than recommending outright removal of the freeway from city plans, a study should be conducted on how to handle the anticipated 35,000 commuters per day who would use the proposed freeway.

Cameron withdrew his proposal but said “we have been subverting people” with the proposed freeway. “People are more important than cars,” he told the commission.

Panel Delays Zoning Action For Oakwood – News and Observer – May 21, 1974

That same year, the Public Works Committee was fully against the highway.

A Raleigh City Council committee Tuesday recommended the junking of plans for the controversial North-South Expressway, which would go through several established neighborhoods.

[…]

Despite strong backing of traffic engineers, the proposed expressway has been the subject of bitter opposition from residents of the Oakwood and Mordecai neighborhoods.

City traffic engineer James D. Blackburn defended the continued presence of the expressway in future city road plans, saying it would be “premature” to remove it.

“No one has ever defined, even in general terms, an alternative to the North-South Expressway,” Blackburn told the committee.

But committee members argued that the price of better downtown access through the expressway was too high if it meant the destruction of neighborhoods.

Panel Moves to Junk Expressway – News and Observer – May 29,1974

It was only a few days later, on June 3,1974, that the Raleigh City Council voted against the expressway. The vote was unanimous.

The Raleigh City Council voted unanimously Monday to kill the major portion of the proposed North-South Freeway because of damage it would cause to existing center city neighborhoods.

The council vote, made with little comment by council members, marks the end of a long fight by residents of the Oakwood and Mordecai neighborhoods near downtown to get the highway link removed from future city road plans.

City Council Kills Planned Road Link – News and Observer – June 4, 1974

All articles are posted at the end including an additional one from May 19, 1975 about Oakwood’s work in becoming Raleigh’s first historic district.

While I’ve read and read about this plan, it is hard to get a sense of just how close we were to actually having this highway on the eastern side of downtown Raleigh. Some older Raleigh residents have told me that a portion of this freeway was indeed built. If you’ve ever exited I-40 at Hammond Road, you have, in fact, driven on a portion of the old North-South Freeway.

Another excerpt from the June 4, 1974 article confirms it:

The council also voted to change the name of the remaining shorter portion of the North-South Freeway, to be located between the proposed Southern Beltline and south to U. S. 70 East. This minor portion would not cut through any existing neighborhoods.

City Council Kills Planned Road Link – News and Observer – June 4, 1974

Notice how Hammond Road awkwardly curves to the west, away from the Bloodworth and East blocks and instead connects to the one-way pairs of Blount and Person.

Today, that wide, six-lane portion of Hammond Road would have been the entrance to the below-grade freeway that could have been.

Articles quoted in this post: