[This post was written in collaboration with James Demby. James is fascinated by how and why different housing types are or are not built. He has been doing an informal study into what has happened in Raleigh housing (ITB specifically) over the last 10 years. See more of that on Twitter.]

Tom Whaley has noticed a lot of changes going on in his neighborhood in the past year. He lives in the North Ridge West neighborhood of Raleigh and worked with some of his neighbors through the city’s Neighborhood Conservation Overlay District process, or NCOD for short.

“Houses being bought, torn down, lots being split up, houses being rebuilt that were much larger and much denser,” Whaley said. “Those types of homes were not fitting into the characteristics of our current area.”

North Ridge West predominantly consists of one- and two-story houses built in the late 1960s through the 1970s. The typical size of a property there is around 20,000 square feet or almost half an acre. If you are doing the math, that comes out to about two houses per acre.

The city’s development code allows for six houses per acre in this area which, in response to Raleigh’s growth in the housing market, allows for the lots to be subdivided for more housing. The neighbors there see this activity as a problem.

“We’re seeking an NCOD due to a point of inconsistency with the zoning and the current build-out,” says Peggy McIntyre, one of the original petitioners and resident in North Ridge West who helped get this process started.

There is nothing wrong with Raleigh citizens getting together and choosing to rezone themselves, but as more and more NCODs are being put into place, it is a good time to ask, “What are the possible impacts of allowing whole neighborhoods to do this?” Since the first one in 1990, NCODs are starting to become a frequent occurrence and their restrictive zoning conditions may have unintended consequences for the city’s big-picture goals.

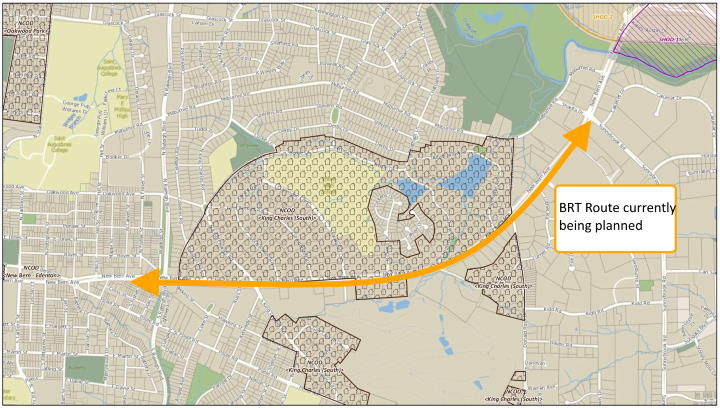

Source: Open Data Raleigh – link. See larger map here.

Above is a map of all NCODs in place in Raleigh. Feel free to browse the map and click on each shape to see a pop-up of information on each one, including the name and date it was put into place.

NCOD Highlights

- Number of NCODs: 20

- Year of first NCOD: 1990

- Smallest NCOD: 24 Acres (North Ridge West)

- Largest NCOD: 557 Acres (Brookhaven)

What is an NCOD?

An NCOD is a zoning tool intended to create a specific result. The City of Raleigh officially defines a Neighborhood Conservation Overlay District (NCOD) as:

A zoning overlay that preserves and enhances the general quality and appearance of neighborhoods by regulating built environment characteristics such as lot size, lot width, setbacks, building height, and vehicular surface area. NCODs generally apply more restrictive standards than base zoning districts.

Character Preservation Overlay Districts – City of Raleigh – link

The city has a number of zoning types that are standard throughout the city. If you are in an R-10, for example, near Crabtree Valley mall or in R-10 zoning near South Park, you have the exact same restrictions as far as the city is concerned. NCODs create specialty overlays to add more restrictions to an area. The NCOD would create additions to the base zoning, so instead of R-10, you would have “R-10 with NCOD conditions.” Each NCOD gets their own additional, custom restrictions and they are listed in our city’s development ordinance, one-by-one.

NCODs are not Historic Overlays Districts. Historic Overlays consider the historical significance of a group of buildings from Raleigh’s past to protect them. NCODs do not necessarily take into account historical aspects of the buildings or structures of an area.

Why would someone want an NCOD?

The most often mentioned reason for wanting an NCOD has been as a response to teardowns. In these cases, a teardown might mean that a smaller, older home is replaced with a new home, larger than the ones nearby.

Lot splits are also a common reason for applying for an NCOD. This happens when an existing lot is divided and the former home removed for two new ones.

Residents near these changes can see an NCOD as a way to stop these types of changes. A desire to keep a neighborhood the way it was, sometimes described as its “character,” is a frequent motivation for requesting an NCOD. Every instance of NCOD so far in Raleigh has been to add a restriction to what can be built in that area.

Affordability has also been used as a reason to put an NCOD into place. With Raleigh’s growth, older homes have been torn down and being replaced with newer ones, resulting in the higher prices that come with new construction. If teardowns can be prevented, the thinking is that the area stays affordable.

As you can imagine, a lot of aspects come up when thinking about the character of a place. Distance between houses, trees, density, and traffic are just some factors in most residents’ idea of neighborhood character.

These can be good, even great things, to protect. Yet the NCOD zoning could be creating conflict in the Raleigh of today.

Controversy and Potential Conflict?

Recently, the most cited reason for adding an NCOD has been to stop lots from being split and old homes from being torn down and replaced by bigger, more expensive ones. That doesn’t sound like the worst idea on the surface, but where this has been controversial is in the execution.

Because of the steps required to obtain an NCOD, these overlays are generally going to wealthier and more organized neighborhoods. So, we are making special protection districts for the areas that already have the most resources, adding privilege.

The other controversy is that NCODs have all been pointed toward restricting housing types. While blocking lot splits, they also block any type of added density. This means that growth will always be pushed somewhere else. If we add restrictions on certain areas, then that means other areas must absorb growth. This rewards the organized communities while adding pressure to other areas.

NCODs never expire, making them a tricky restriction when planning for the future. The situation around an NCOD may change dramatically, but it now takes 50% of the people in that NCOD to make any new change to even a few properties.

The King Charles NCOD is a good example of this. It was planned with restrictions including a 0.7 acre lot minimum at a time when the neighborhood expected most of Raleigh’s growth to go in another direction. Then years later, the nearby New Bern Corridor was selected for Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and now roughly a third of the area around this big investment in transit will be locked down with an NCOD requiring 0.7 acres per lot. This is now in conflict with the need for density near transit.

An interesting side of the controversy around NCODs is whether they protect affordability. In the immediate short term they may, so when neighbors see teardowns and McMansions the NCOD is seen as a way to keep the older more affordable homes intact.

On the other hand, NCODs are not being used to encourage additional smaller units that could be more affordable; they are usually just restricting the number of homes in the area to stay exactly the same. In a growing city and desirable neighborhood, this could mean that even though the older homes are less expensive than new ones, they now see their value grow even more because they are the only option for the area. In the last few NCODs that have been brought up by council, the older homes in the area have already been worth over $350,000 or higher.

Wrapping Up

Thankfully, there has been some talk at the council level and in planning commission that the NCOD zoning tool may not be generating the results it was designed to create. This conversation needs to be pushed further and with a higher priority as NCOD applications are rolling in, with one every year since 2016. Two have been adopted this year (2019), and a third is on pace for approval in 2020.

With NCOD’s, we are allowing Raleighites to self-restrict in a way that may be giving them an advantage over other areas of the city. This process is not equitable, because the most organized and most diligent get the rewards.

The process also pits neighbors against each other due to the fact that only 51% of an area needs to agree to an NCOD. This process therefore rewards homogeneous areas versus those that are diverse. It also sets in place restrictions for future generations that may want different things.

There may come a tipping point where we’ve custom-zoned too much of the city. Currently, 3.35% of the city is inside an NCOD. Raleigh is planning for growth along transit corridors, corridors that currently have NCOD restrictions in place. This only makes it more difficult to plan for proper housing close to transit.

Fighting for neighborhood protections doesn’t necessarily need to stop altogether in Raleigh. It’s just time to start thinking about the potential impacts these “frozen in time” restrictions have toward Raleigh’s future.